© 2016, BSM Consulting

6

Basics of Glaucoma

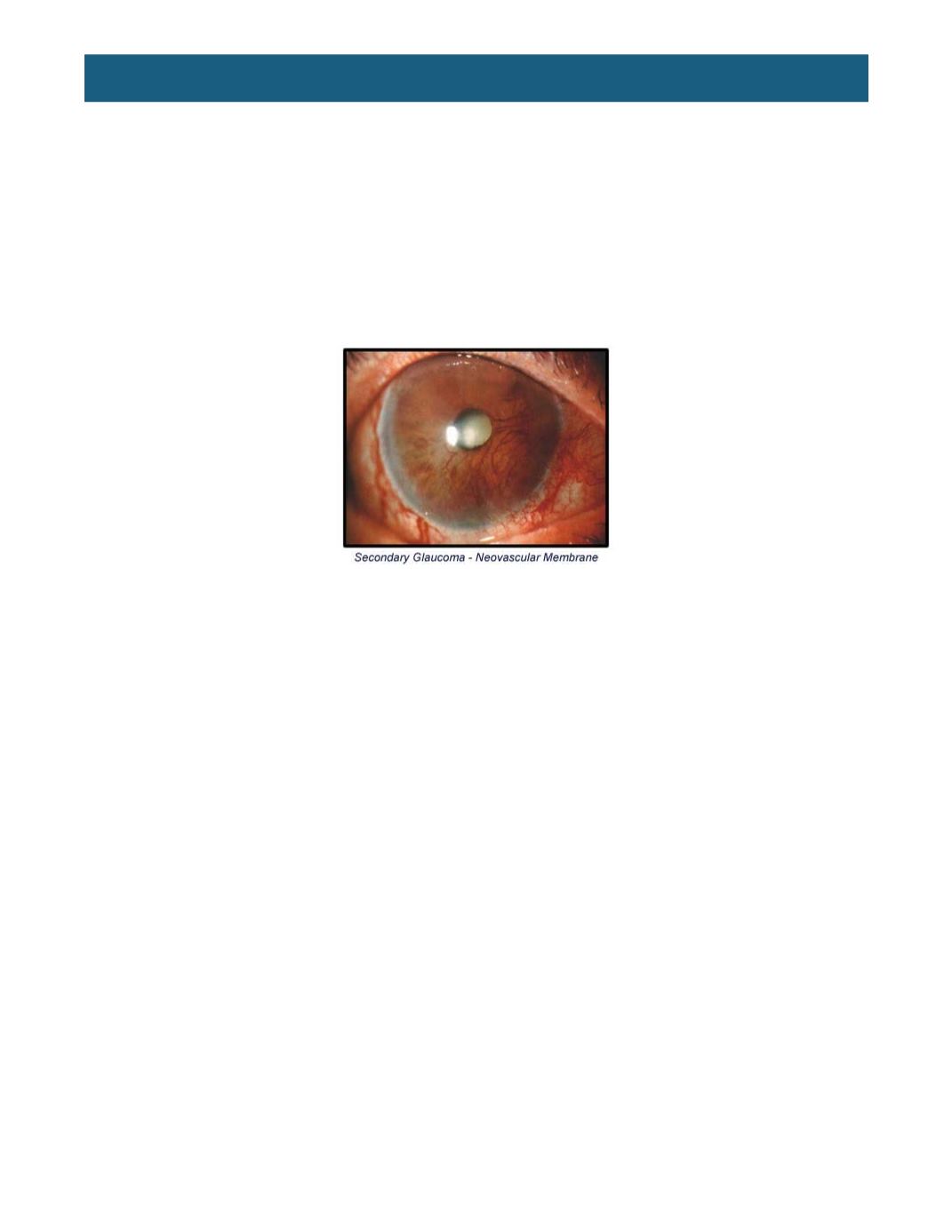

Secondary Glaucoma

Physicians might diagnose secondary glaucoma when they believe that the disorder results from an

unrelated ocular or systemic disease. In some cases it can result from adhesions (peripheral anterior

synechiae) between the iris and the trabecular meshwork, leading to chronic angle-closure glaucoma,

inflammation in the eye, dislocation of the lens, red blood cells, or ocular tumors. Ocular trauma may also

result in an increased pressure that requires long-term control. The use of certain medications, such as

corticosteroids, may lead to increased IOP. Patients with this type of response are known as “steroid

responders” and subsequent withdrawal of the steroid may result in a reduction of the IOP. Additionally, in

some diabetic patients and in those with high blood pressure or arteriosclerosis, a membrane of abnormal

new blood vessels may develop and cover the trabecular meshwork, causing an aqueous buildup. This

type of secondary glaucoma is known as neovascular glaucoma.

Congenital Glaucoma

Congenital glaucoma is a rare but potentially blinding eye disease, which occurs in only about one in

10,000 births or appears any time during the first three to four years of age. Most often it is diagnosed

before a child’s first birthday.

In congenital glaucoma, an abnormal drain (trabecular meshwork) in the eye causes higher-than-normal

eye pressure. The drain is defective and functions poorly. Generally speaking, the younger the age at

which the glaucoma appears, the more difficult it may be to treat successfully.

Before the age of 3, the wall of the eye is very soft and elastic. Therefore, when the IOP rises in

congenital glaucoma, the eye enlarges and becomes buphthalmic. Congenital glaucoma can affect only

one eye; therefore, a parent, family member, or pediatrician might notice asymmetric buphthalmia, often

resulting in a consultation with an ophthalmologist. Bilateral cases may be more difficult to identify, as the

child may exhibit large, beautiful eyes with relatively normal appearance, or might have corneal clouding.

Symptoms of congenital glaucoma include:

•

Photophobia

•

Tearing (epiphora)

•

Blepharospasm

After the age of 3 to 4, the eye is less elastic and does not increase in size when the pressure rises.

Although the glaucoma most commonly affects both eyes, it is often more severe in one eye than the

other.

In congenital glaucoma, eye surgery is usually necessary, as treatment with eye drops helps only

temporarily. Fortunately, surgical treatment, particularly in glaucoma that develops after the age of 6

months, is often successful in lowering IOP permanently. Surgery can open the poorly functioning drain,

exposing the deepest portions of the drain to the aqueous fluid. Two procedures, goniotomy and

trabeculotomy, are specifically designed to treat congenital glaucoma. Fortunately, when diagnosed and