© 2016, BSM Consulting

4

Basics of Glaucoma

Low Tension Glaucoma

More difficult to diagnose is low (or normal) tension glaucoma. As its name implies, tonometry readings

will be in the statistically normal range, under 21 millimeters of mercury. Pachymetry may often reveal a

thinner-than-average corneal thickness (less than 535 microns). The physician might notice an increased

CD ratio or a small hemorrhage on the optic disc (Drance hemorrhage), alerting the physician that further

testing might be necessary.

This form of open-angle glaucoma often requires greater effort to manage the intraocular pressure.

Because the pressure is under 21 at the time of diagnosis, the target pressure will often be lower for a

patient with low tension glaucoma than for a patient with primary open-angle glaucoma.

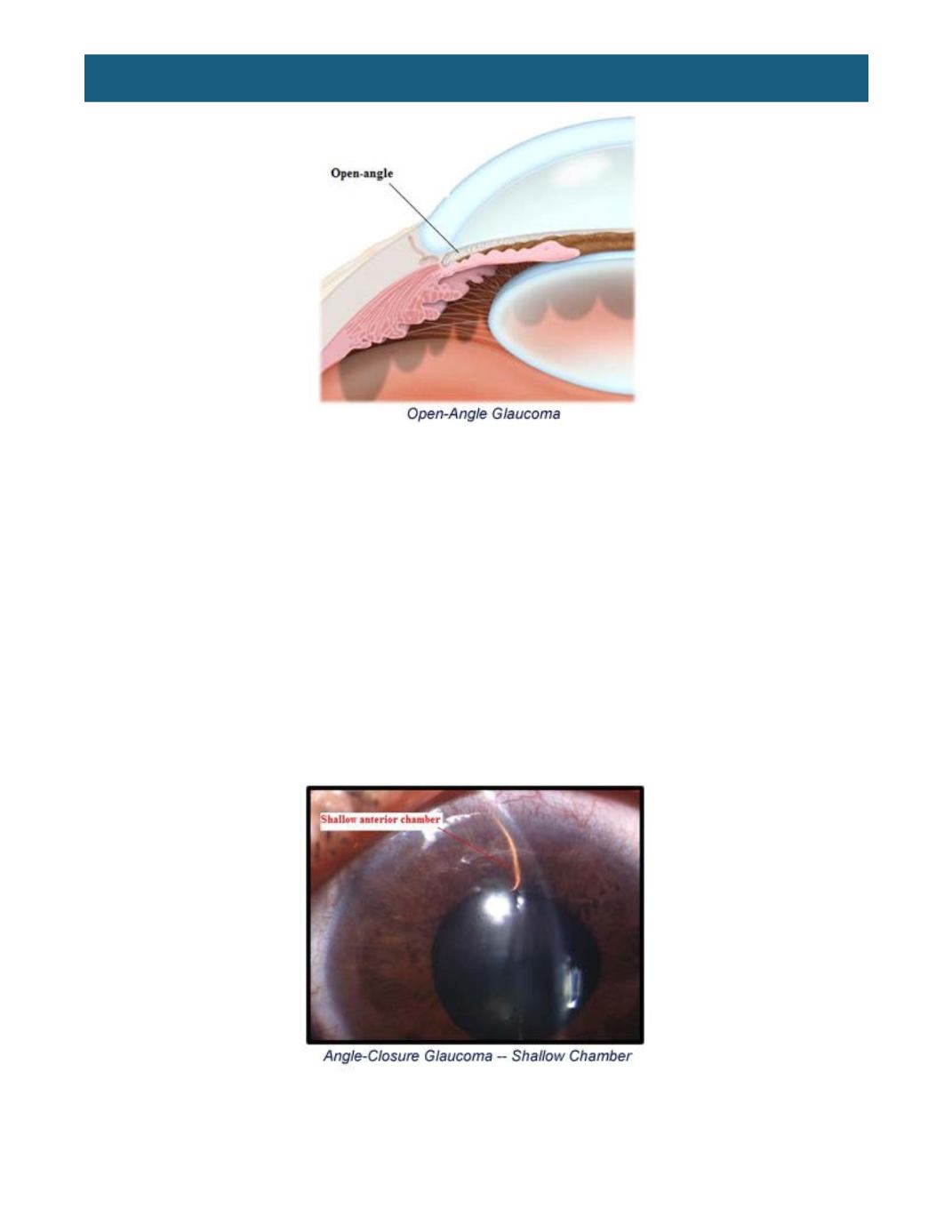

Narrow-Angle/Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Far less common than open-angle glaucoma is narrow-angle, or angle-closure, glaucoma. These types of

glaucoma are associated with a shallow anterior chamber and reduced space between the front of the iris

and the back surface of the cornea. Located 360 degrees around the cornea at the iris, the anterior

chamber angle is shallow in narrow-angle glaucoma, but there is adequate drainage of aqueous in most

instances.

As a person ages, the lens becomes larger, which further narrows the angle. When the pupil is normal

size (2-4 millimeters), the aqueous can pass from the posterior chamber, through the pupil, and past the

front of the lens to the anterior chamber with little difficulty. However, when the pupil is dilated to the mid

position (5-6 millimeters) in patients with narrow angles, the iris comes into contact with the front of the