© 2016, BSM Consulting

14

Modern Glaucoma Surgery

resistance to aqueous outflow. In this latter case, there is usually a large bleb. All of the

approaches described for bleb leaks can also be applied to overfiltering blebs, including the

possibility of surgical revision. If the anterior chamber is shallow and the IOP is high, there is

cause to suspect aqueous misdirection syndrome. This occurs when aqueous flows posteriorly

into the vitreous cavity, pushing the vitreous and lens (crystalline or implant) forward, flattening

the chamber. Since aqueous is not exiting through the newly created drain, the bleb is usually low

or flat. Aqueous misdirection syndrome will often resolve with high-dose atropine therapy, may

require an Nd:YAG laser application to make a hole in the anterior vitreous to create a pathway

for aqueous to flow back forward (which can only be performed in pseudophakic or aphakic

eyes), or in more recalcitrant cases, surgical vitrectomy.

•

Shallow or flat bleb.

This can occur when there is a bleb leak (in which case IOP is usually low) or

if the surgical drainage hole is blocked, preventing aqueous from reaching the bleb (in which case

IOP is usually high). Bleb leaks are addressed previously in

Wound leaks.

Outflow obstruction in

the immediate postoperative period is usually due either to a blood clot, a fibrin clot, or too-tight

suturing of the scleral flap. All are serious risk factors for bleb failure, because if there is no

aqueous in the bleb, the conjunctiva is in direct contact with the underlying sclera and can scar

down to it, preventing future bleb formation once the obstruction is resolved. A blood clot can be

resolved by injecting tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), a potent clot-dissolving medication,

directly into the anterior chamber, although this runs the risk of a large hyphema if the vascular

defect that caused the clot has not yet healed under the clot. A fibrin clot can often be washed

away by burping the surgical site. This is performed by gently pressing a sterile instrument (such

as a scleral depressor) against the sclera (through the conjunctiva) adjacent to the edge of the

scleral flap. The goal is to transiently lower the resistance to outflow, so that a small burst of

aqueous through the surgical drain will wash the fibrin clot away. If the problem is that the flap

has been sutured too tightly, the argon laser can be used to cut one or more of the sutures

holding the flap down (again, through the conjunctiva, using a special lens designed for just this

purpose) to reduce the resistance to outflow. Some surgeons prefer using releasable sutures for

the scleral flap. These do not require cutting with a laser—they are placed in such a way that the

surgeon can grasp one externalized end at the slit lamp and pull it out, loosening the scleral flap.

If these measures fail, the scleral flap may be scarring down to its bed. In this case, the bleb may

require needling. A 30-gauge needle is inserted through the conjunctiva and advanced under the

scleral flap, then tilted slightly to elevate the flap and peel it free from the bed. The needle tip can

also be advanced through the drainage hole into the anterior chamber to clear any scar formation

in that location. This procedure is typically followed by several daily subconjunctival injections of

5-FU to minimize the risk of recurrent scarring. Needling can be performed at the slit lamp.

•

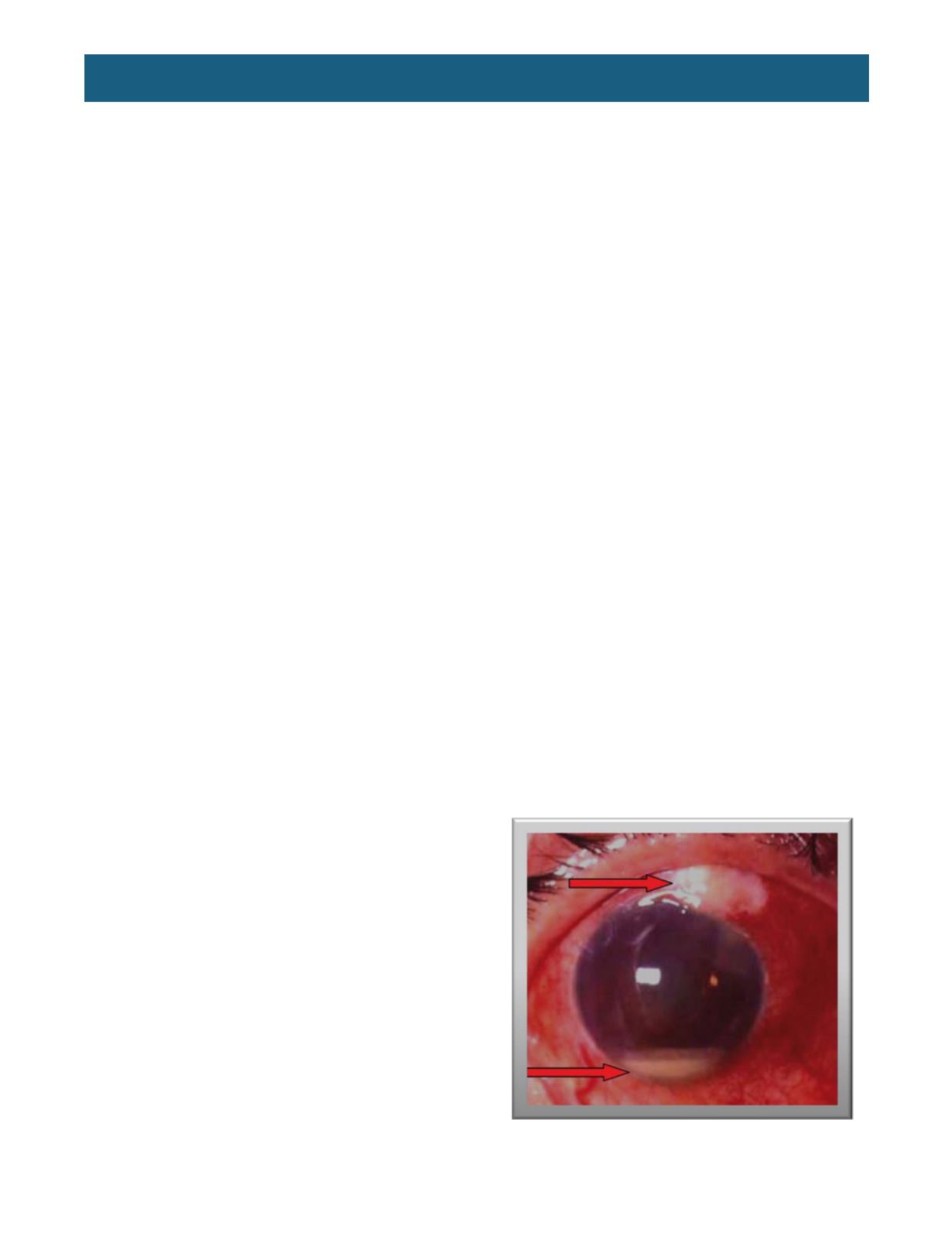

Infection.

Blebitis and/or endophthalmitis is

the worst-case scenario for bleb surgery.

Endophthalmitis due to contamination at the

time of surgery typically presents within 48

hours; blebitis/endophthalmitis related to a

bleb leak can occur any time postoperatively

as long as the bleb is functional. The patient

will present with a red, painful eye and

decreased vision. There may be visible pus

on the eye surface or in the bleb, and

examination will reveal a hypervascularized

bleb, cell and flare and possibly a hypopyon

in the anterior chamber, and possibly

inflammatory debris in the vitreous (

Figure 8

).

This is an emergency and can lead to loss of

the eye if not appropriately addressed. A

vitreous biopsy is required to culture to

identify the organism causing the infection,

followed immediately by high-potency broad-

spectrum antibiotics delivered topically,

intravitreally, and orally. It may seem tempting

to give the antibiotics before all else, but if the

Figure 8.

Blebitis/endophthalmitis with hypopyon in

the anterior chamber.

(From

http://www.ijo.in/viewimage.asp?img=IndianJOphthalmol_2011_59_7_131_73689_u15.jpg)